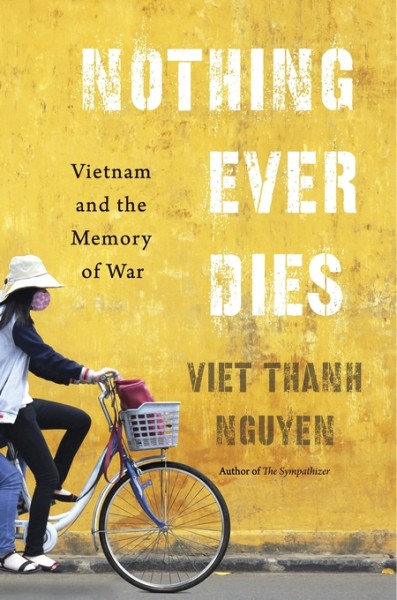

The second book out from author Viet Thanh Nguyen, Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War, is a sharp non-fiction work that deals in the theoretical world of remembrance, forgetting, humanity, and its lack. Nguyen is much in the news these days after his first book, The Sympathizer, won a Pulitzer–an excellent and witty novel of politics, intrigue, and one man’s twisted war experience.

Nothing Ever Dies is also an excellent book, but written in a different style for a different purpose. In many ways, it complements The Sympathizer, approaching some of the same topics but from a scholarly angle. Weaving together philosophy, history, personal narrative, and other strains, Nguyen asks readers to carefully consider how war is remembered–by victors, by losers, by humans, and by history. The Vietnam War is the centerpiece. Though covering complex topics, Nguyen’s writing is accessible and flows smoothly (no surprise from a skilled novelist). It is the ideas behind the words that force your brain to work–to be thoughtful and critical of your own perceptions. As he explains in the opening lines of the introduction:

This is a book on war, memory, and identity. It proceeds from the idea that all wars are fought twice, the first time on the battlefield, the second time in memory.

I won’t tell you that reading this scholarly work is easy, but it is worthwhile. I’m a bit predisposed to being interested in Nothing Ever Dies, long intrigued by how memory of historical events influences our world today. So I can readily say it’s the kind of book I can imagine reading over and over and getting something different each time.

But even those with an interest in how we see ourselves, through culture, history, and memory, will find this book enlightening and thought-provoking. How do we remember? How should we remember?

What I look for and argue for in this book is a complex ethics of memory, a just memory that strives both to remember one’s own and others, while at the same time drawing attention to the life cycle of memories and their industrial production, how they are fashioned and forgotten, how they evolve and change.

The book traverses both the theoretical ground outlined above (and evidenced by chapter titles such as “On War Machines” and “On Powerful Memory”), is also grounded in particular cultural moments and events, such as the author’s own search for and interpretation of memorials in South Vietnam, Cambodia, and elsewhere. In considering the role of popular culture and writings, he even investigates his own role as a novelist and scholar. It is this openness to inquiry and criticism that characterizes the entire book.

Nguyen interrogates war, war’s participants, war’s re-tellers, war’s memory…as much about these broader categories as it is about the Vietnam War specifically. It’s provocative by way of being thought-provoking, of forcing its readers to look at themselves and their complicity both passive and active in some of the issues he lays out. Valorizing one’s own side while demonizing or forgetting the losses of the other side, for example. With each chapter, I was left chewing on new ideas and greater awareness of the importance of being cognizant of how we talk about war.