Golden State Warriors’ 2026 Lunar New Year Celebration night came early this year on Tuesday, January 20th, although the 2026 Lunar New Year isn’t until Tuesday, February 17th. I guess within a month is still okay! The last time I had attended this annual Warriors celebration night was back in 2024.

Golden State Warriors’ 2026 Lunar New Year Celebration night came early this year on Tuesday, January 20th, although the 2026 Lunar New Year isn’t until Tuesday, February 17th. I guess within a month is still okay! The last time I had attended this annual Warriors celebration night was back in 2024.

It’s great that the Golden State Warriors and other NBA teams have such theme nights. San Francisco is 37% Asian and the San Francisco Bay Area overall is approximately 27% Asian American. The Warriors get local Asian organizations to perform in front of their audience.

The Lunar New Year celebration first started with a pre-game performance at 6:30 PM (the game started at 7:00 PM) with a terrific performance by Huaxing SF:

My photographer and I, as well as others, were truly impressed. We thought afterwards this performance was the best of the evening. It’s unfortunate that many attendees had not yet arrived yet to see the performance.

Right before the singing of the national anthems and introduction of the teams, Executive Director of Oakland Chinatown Chamber of Commerce, Linyi Nikki Yu, was the honorary Bell Ringer for the evening.

Before the start of the game, I believe it was Huaxing SF that did the pre-game performance that sang both the Canadian and the U.S. national anthem. The Warriors were playing the Toronto Raptors.

Continue reading →

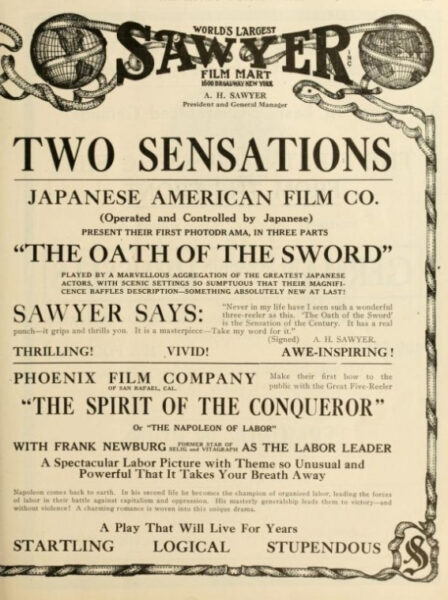

The Oath of the Sword, the oldest Asian American film, has been included into the US National Film Registry. Produced in 1914, it is the story of a Japanese couple separated when the man goes to study at UC Berkeley. Studying at UC Berkeley? Definitely very Asian American!

The Oath of the Sword, the oldest Asian American film, has been included into the US National Film Registry. Produced in 1914, it is the story of a Japanese couple separated when the man goes to study at UC Berkeley. Studying at UC Berkeley? Definitely very Asian American!

We have news of

We have news of

Even while many people were upset about Bad Bunny’s Superbowl performance in Spanish, songs with Korean words have been

Even while many people were upset about Bad Bunny’s Superbowl performance in Spanish, songs with Korean words have been

Every year, Apple releases a Chinese New Year short film that is shot on their latest iPhone, and every year I look forward to the story that is created. This short for 2026 is called

Every year, Apple releases a Chinese New Year short film that is shot on their latest iPhone, and every year I look forward to the story that is created. This short for 2026 is called  Excited to see Asian Americans in the 2026 Winter Olympics? There are definitely some interesting stories regarding Asian Americans in Milano Cortina.

Excited to see Asian Americans in the 2026 Winter Olympics? There are definitely some interesting stories regarding Asian Americans in Milano Cortina.

We have talked about Asian

We have talked about Asian