As an incoming Freshman at UC-Irvine, I was amazed to see that more than half the tables at the student activities fair were ethnic, not interest, organizations. There were three Chinese groups, a Korean students association and a Korean Christian Association, and tables for nearly every Asian country, along with a few token groups for the 40% non-Asian student population (Hispanic Students Association, Young Baptists). Upperclassmen sitting at each booth were scanning the crowd, looking for their ethnic kin, ready to pounce. They didn’t seem to want to have me join.

Then, at the end of the row, a pair of eyes came looking right for me. An Indian from the table with a sign, in English but with horizontal lines above the letters mimicking Hindi script, “Indian Sub-Continental Club.”

“Hey there, come to our first meeting this Wednesday,” he said, thrusting a yellow flyer into my hand.

Intially I didn’t want to go, but after seeing that all my fellow dormmates were attending their ethnic clubs first meetings, I succumbed to pressure and went. It was in the same lecture hall that my Humanities course was. Over 300 Indian-American students showed up. I found an empty seat, already feeling out of place.

The president of the club went up on stage and began speaking, smattering random Hindi words that I didn’t understand into his speech, talking about holidays I’d never heard. Diwali?

“We’re going to pass around sign-up sheets for different activities. Put your name down if you are interested,” he said. I was near the front, so soon my neighbor, a short, light-skinned girl, handed the sheets to me.

One was for Diwali, and the other two bewildered me. Garba? Bhangra? I thought I knew my culture well; after all, I could speak Telugu and knew how to cook some Andhra dishes. But what was this? I turned to the girl sitting next to me.

“You know what this is? Bange..grra?” I asked her. She turned and looked at me with eyes of amazement.

“You don’t know what Bhangra is?” she exclaimed.

The guy sitting in front of her turned around, “Are you serious? You don’t know what Bhangra is?” They both started laughing.

“It’s a Punjabi dance,” she said. “How can you not know that?”

Punjabi? But now, I was too scared to ask any other questions. I sat there, lost and confused, through the orientation, the events calendar, and the Bollywood movie quiz.

I never went to an Indian club meeting ever again, and didn’t make any Indian friends at UCI.

North India is as foreign of a culture to me as China, Korea, or Russia, because I grew up completely South Indian. Kansas City has a sizable Telugu (my native language) population, so as a child my family would regularly attend Telugu events. Even the priest at the local temple was South Indian, and he spoke Telugu fluently. Our trips to India focused on my mom’s homewtown of Hyderabad and my father’s hometown of Bangalore, both in the South. I knew nothing of Bollywood, Hindi, and, until finishing college, never even had Naan or Tandoori before.

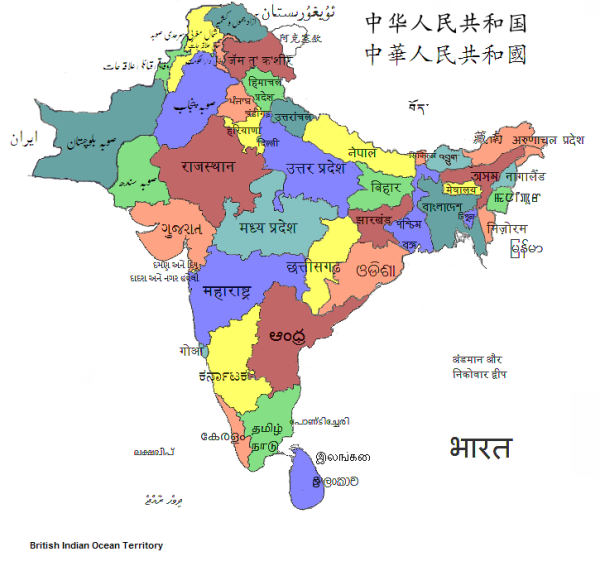

India, as a country, was an invention of the British, as no pre-colonial empire ever controlled the vast subcontinent. An estimated 415 distinct languages are spoken in India, which is also the birthplace of four major world religions (i.e., Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism) and the last home of the world’s oldest religion (Zoroasterism). The ancient name for India, Bharat, denoted a vast land, a continent rather than a country.

In this complexity, though, the biggest divide is between the North and South of the country. Language, culture, cuisine, even gender balances differ between the two regions. South Indian scripts, wavy and circular, look more like those of Southeast Asia than North India. There are even seperate film industries in the South: in an average year, there are as many Telugu and Tamil films made as there are Bollywood Hindi films, and though they make little inroads in the West, they enjoy popularity in parts of Southeast Asia and Africa.

Hindi, Bengali, Nepali, and Punjabi are Indo-European Languages, distantly related to English, Farsi, and Russian, the most widely spoken language group in the world. South Indian languages are of distinct Dravidian Family heritage. When I hear Hindi spoken, I understand just as much of it as I do Thai or Russian — a stark contrast to Tamil, another South Indian language, of which I can pick up about 20%. This is why, when I was in Nepal several years ago, I found that Nepali had more words in common with Spanish than Telugu.

In America, 90% of Indian Americans in my generation trace their roots to the North, mostly Punjab and Gujarat, where Hindi is the lingua franca. My uniqueness was ridiculed at UCI because I didn’t fit their narrow idea of “Indianess.” I was considered ignorant or, worse, a “coconut” (a South Asian “banana”). Instead of comforming to their idea of Indian, I took pride in my own language and culture. I learned that Telugu was one of the oldest written languages in the world, with a rich literature that dated back over 600 years, as long as that of English, and began practising speaking more often with my Grandma, even beginning reading lessons.

In California, though, it wasn’t just Indians who were forcing me to fit a certain image. Non-Indians would come up to me and say Namaskar, a Hindi greeting, or tell me that their favorite Indian dish was channa or daal, neither of which I’d ever heard of (in Telugu, the words are Senaga Puppu and Sambar). Few wanted to hear about how South Indian culture was unique. They were more interested in proving their own cultural knowledge than being open to learning.

It’s common among Asians to feel this pressure from society. But as a minority within a minority, it came in two layers. It forced me to be an outsider.

This shouldn’t be how it is. Few countries in the world are homogenous. In Asia, only Korea has a true, unifying language. Every other country is a fluid mix of languages, religions, and ethnicities. Double minorities like me exist everywhere, but we seem to be ignored in the overly pervasive – and completely wrong – idea that national identity and culture are interchangeable.

Last year, I met a Chinese-Canadian girl from Quebec from a Hokkien family, and her experiences with Mandarin and Cantonese speaking Chinese students in Montreal paralled my experiences in California. Today, her friends are mostly French-Canadian, and to an outsider, she may seem white-washed, but in reality, she’s still possesses a deep interest in her culture and plans to someday visit China to improve her Hokkien. Likewise, in the next year or two, I will spend time in South India learning classical Telugu.

Instead of narrowly defining identity, a more open attitude could allow for greater expression. I’m happy to learn about North Indian culture just as I was happy to backpack for six months in Southeast Asia and learn Indonesian, but I detest being expected to know it. Thus, I still don’t watch Bollywood Films, but have a strong appreciation for classical Carnatic music and devour readings on Indian cultural history. I still don’t know much Hindi but have improved my Telugu dramatically since Freshmen year.

Does that make me any less of an Indian? Or just more of an Asian? For some reason, I doubt the Indian club would be any more accepting of me now as 10 years ago.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons