As a child growing up in America, I thought of myself as not-American. In America, I was Taiwanese, I was Chinese, I was Asian. Though I pledged my allegiance to the American flag alongside my classmates of various ethnic and heritage backgrounds, the concept that I had to be White to be American had seeped into my conciousness from popular media, from society, from my fellow Americans.

Ironically, I was most American when I was not in America. In Taiwan, my heritage country, my chopsticks would get taken away and I was always offered milk and hamburgers because that’s what American kids eat. It seems that a fish knows most that it’s a fish when it is out of water.

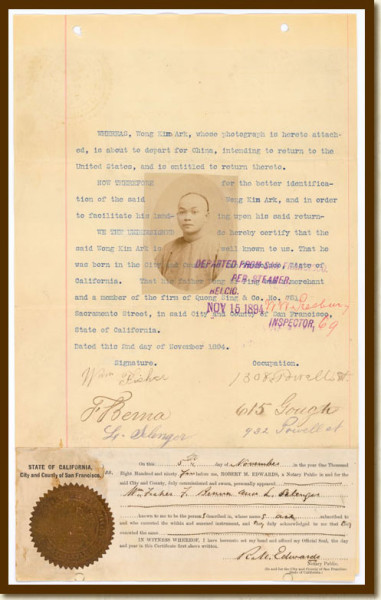

[Image from Documented Rights]

That was definitely also the case for Wong Kim Ark. Not only did leaving America make him an American, it forced the United States of America to define and defend what it means to be an American citizen.

The Chinese Exclusion Act

On May 6, 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act which made it so that “the coming of the Chinese laborers to the United States be…hereby, suspended; and during such suspension it shall not be lawful for any Chinese laborer to come…to remain within the United States.” In other words, this act made it so that no new Chinese people were allowed here in the United States. This act was a product of anti-Chinese sentiment during that time period due to anger and resentment over Chinese laborers being willing to work for lower wages and taking jobs. It was also a product of just general racism towards the Chinese in America.

The Chinese Exclusion Act also included a deportation order, that “any Chinese person found unlawfully within the United States shall be caused to be removed therefrom to the country from whence he came, by direction of the President of the United States, and at the cost of the United States, after being brought before some justice, judge, or commission of a court of the United States and found to be one not lawfully entitled to be or remain in the United States.” Due to a general lack of documentation and record keeping at the time, this made it possible for people of Chinese descent to be targeted and deported.

Further, the Chinese Exclusion Act also made a clear stand on whether the Chinese could become citizens, “that hereafter no State Court or court of the United States shall admit Chinese to citzenship; and all laws in conflict with this act are hereby repealed.” This was an unequivocal block to citizenship for anyone from China. But did it apply to those people of Chinese descent who were born here in America?

Wong Kim Ark

Wong Kim Ark was born in 1873 in San Francisco, California, and he had lived at the same residence his whole life. His mother and father were legallly subjects of the Emperor of China. When he was born, his parents were living permantently in the United States. However, in 1890, his mother and father left for China. Following his parents, Wong also left for China, but only for a temporary visit and planned to return to the U.S., which he did on July 26, 1890 on the Steamship Gaelic. On this return, he was allowed to enter the U.S. because, despite being of Chinese descent, he was a native-born citizen of the United States.

In 1894, Wong went on another temporary visit to China, also planning to return to the States. When he returned in August of 1895, this time, he was denied re-entry to America because he was not recongized to be a citizen of the United States. Wong had never renounced his allegiance to the United States. These were the accepted facts that were submitted to the Supreme Court when Wong sued the United States of America for his right to citizenship.

VS. United States of America

On July 9, 1868, a majority of the states ratified a change to the Constitution of the United States, which included in Section 1 that “all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.” This very clearly stated that anyone who was born in the United States, as Wong Kim Ark had been, would be an American citizen. However, with The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, proof of birth was key in order to make a case for citizenship. In a time when birth certificates and other forms of documentation were not regularly kept, this was a tall order.

However, Wong was able to procure such evidence. Due to racists attitudes of the time, it was important that a non-Chinese speak for him in order to be valid, and fortunately, Wong had three of such individuals. On November 5, 1894, three non-Chinese descent individuals in a document notorized by a Rob Edwards declared Wong had been born in San Francisco. W. Fisher, F. Berna, and L. Selenger assured that “we the undersigned do hereby certify that the said Wong Kim Ark is well known to us. That he was born in the City and County of San Francisco, State of California. That his father Wong Si Ping was a merchant and member of the firm of Quong Sing & Co. No. 751 Sacramento street, in said City and County of San Francisco, State of California.” Although there existed such clear evidence of his birth and residence in the US, evidence that was even accepted by the United States, the case was still taken to the Supreme Court.

E Pluribus Unum

Despite the challenge, the Supreme Court upheld the law of the land, that the Constitution takes precedence over the Chinese Exclusion Act that Cogress passed. In Justice Gray’s official opinion of the court, he wrote that “if [Wong] is a citizen of the United States, the acts of Congress, known as the Chinese Exclusion Act, prohibiting persons of the Chinese race, and especially Chinese laborers, from coming into the United States, do not and cannot apply to him.” The result of Wong Kim Ark vs. United States of America was a reaffirmation that “all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.”

The attempt to deny an American of Chinese descent of his birthright to American citizenship based soley on the color of his skin was unsuccessful. Thanks to this landmark Super Court decision, the United States was able to clarify the question of race when it came to becoming a citizen. Although The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 made it impossible for any Chinese from China from becoming a citizen, it did not prevent those of Chinese descent born in American from becoming American citizens. This set the precedent that protected the birthright citizenship of any child born in the United States regardless of his or her heritage, ensuring that America would definitely be e pluribus unum, “out of many, one”.

References

* Archives.gov. The Constitution: Amendments 11-27 Transcript. Retrived from www.archives.gov/exhibits/charters/constitution_amendments_11-27.html on August 9, 2015.

* Chang, Iris (2003). The Chinese in America. Penguin Books.

* Edwards, Rob (November 5, 1894). Wong Kim Ark’s Departure Statement. City and County of San Francisco State of California. Retrieved from www.archives.gov/exhibits/documented-rights/exhibit/section2/detail/departure-statement-transcript.html on August 9, 2015.

* Ourdocuments.gov (May 6, 1882). Transcript of Chinese-Exclusion Act. Retrived from www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?doc=47&page=transcript on August 9, 2015.

* United States v. Wong Kim Ark (March 28, 1898). Legal Information Institute, Cornell University Law School. Retrived from http://www.lawcornell.edu/supremecourt/text/169/649 on August 9, 2015.

* Wu, Frank H. (2001). The Chinese Experience: Eyewitness: “Rejecting those racial arguments, the Court based its ruling on the Fourteenth Amendment.” Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved from www.pbs.org/becomingamerican/ce_witness17.html on August 9, 2015.