In April of this year, I was asked by Southern California Public Radio to do a presentation about my family as part of their new series called, Unheard LA. The following is the video from my talk, followed by my original speech (broken into two parts). Please note, the text is from the original draft of the speech, so at points is considerably different than the actual talk I gave.

https://www.facebook.com/KPCCInPerson/videos/1461691680518601/

CHAPTER 1: My hero

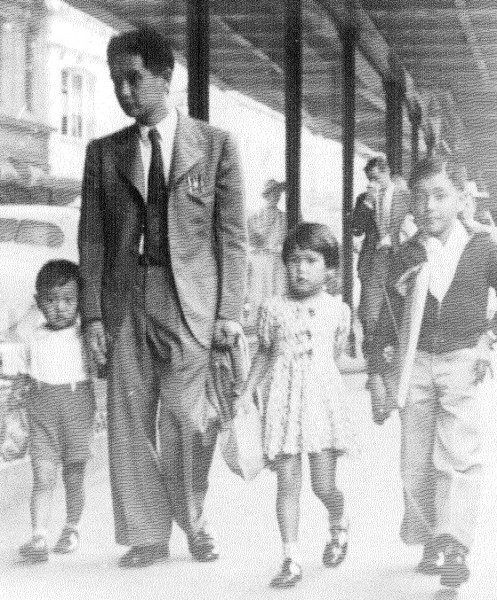

My father’s name was Walter Sakai. He was my hero. I know a lot of people say that about their dad’s, and I’m sure they mean it, but I had a special relationship with him. You see, he had a stroke when I was born that left him unable to work. Because of it, he took care of me and we got to be very close.

The one part of him that I never understood was what happened to him when he was in “camp.”

CHAPTER 2: My understanding of what happened

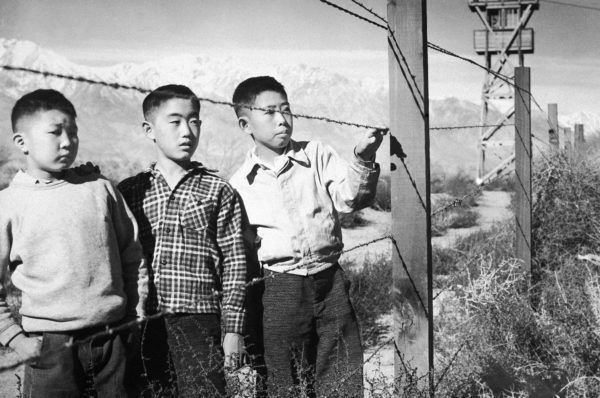

“Camp” is shorthand in Japanese American for the “internment camp” or more accurately, “concentration camp.” I know people always freak out when they hear that word. This is no disrespect to what happened in Europe, because those were much worse, those were death camps. What happened here is the picture book definition of a concentration camp. In fact, the people in government originally called it a concentration camp. Calling it an internment camp is a euphemism. Another euphemism from that time is “relocation” instead of what it really was an “incarceration.”

One of the earliest memories I have of my father was him trying to make sense of what happened to him when he was a child. Time, sickness, and age had worn down his memory until he had only three left of his time in camp.

- His dad worked for the “Japanese government” and that’s why they were taken.

- That they had been in the Tule Lake, Northern California camp.

- That the food was really bad.

No one else in the family seemed to remember much more. When I asked my uncle, the oldest child in my father’s family, he told me they were in Topaz, Utah. And my aunt, my dad’s older sister, said they were Crystal City, Texas. My aunt also remembered a swimming pool at Crystal City! A swimming pool? In a concentration camp? What’s unusual about all of this was that most Hawaiian Japanese were not taken to the camps. So why them?

The one thing everyone said was that neither of my grandparents wanted to discuss what happened and that my grandmother would have a visceral reaction when she thought about her time in “camp.”

CHAPTER 3: Trying to find his story

Just because my father wasn’t sure what happened to him, didn’t mean “camp” didn’t keep popping up in our lives.

In 1988, my father received his twenty thousand dollars and an official apology from the government. I remember how much it meant to him when he got it. It was vindication that what happened was wrong.

A few years after that, my father took me to the Japanese American National Museum, which was relatively new when we went. I only remember one thing from the trip, my father looking up his father (my grandfather) in the library. The records indicated that my grandfather was a mechanic. My father didn’t like that! He said he wasn’t a mechanic and we left.

I didn’t see this at the time but my father was yearning to find out answers as to what happened and why.

CHAPTER 4: My path to the story

It wasn’t until I started working at the Japanese American National Museum in my mid-twenties that I started to ask questions about what happened. Being around Japanese American history and culture as well as people who had been in camp, I suddenly needed to know my family’s story. Everyone who knew—including my father—had passed away or didn’t remember much, so I started to do research. I wrote to the National Archives, Dept. of Justice, and the FBI…

CHAPTER 5: The story

… and this is the story I found… I hope this puts my father’s soul to rest.

My grandfather was a NISEI, a second generation, or in other words an American citizen.

My father had been right, my grandfather worked for the Japanese government. He was a clerk in the consulate’s office in Honolulu which was the equivalent of working for the Taliban in New York City right before 9/11. Not a great place for him to have been.

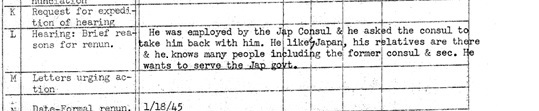

The FBI believed my grandfather was pro-Japanese with anti-American sentiment, more “old-time Japanese” than anything else.

My grandfather was taken by the FBI and sent to Sand Island in Hawaii. He was accused of three things:

1. In 1937, he and another consulate official took a camera from a naval intelligence officer who was taking a picture of a Japanese ship.

2. During a hearing, he admitted seeing other consulate officials acting suspiciously and did not report it to the proper authorities.

3. And probably most damming, he was paid to burn paperwork on August 1, 1941.

The charges were vacated but the government considered him so much of a danger thhat he could not be released. So, they sent him (and my family) to the camps on the mainland.

To be continued…

Follow me on Twitter @ksakai1.