Introduction

The history of Chinese immigrant laborers began with the California Gold Rush, where thousands of hopeful workers migrated to the US in hopes of attaining wealth and being able to send some of that wealth back home to their families. What they met here in the US were miserable working conditions, rampant discrimination, and a country hostile to their discrimination. Stripped of their rights and dignity, Chinese laborers sought protection through labor unions, creating their own and seeking assistance from others. Here, they were able to fend for themselves, dispel underhanded exploitative practices, and find greater advocacy for their own social rights. However, the relationship between Chinese laborers and organized labor is not neatly defined and has fluctuated from union to union and from time period to time period. At times where they found aid and assistance from unions, they found violence and hostility from another; at times when they needed unions to provide them benefits, they came to no longer depend on them in recent years. In this essay, I will argue that the relationship between Chinese immigrant workers and American labor unions is largely negative, albeit with some positive elements. This essay seeks to explore the relationship between Chinese workers and labor unions in the US, how unions were both a source of help and hostility, and why unionization rates among Chinese workers have plummeted as of late. I will examine these topics in a linear temporal fashion, beginning first with the labor unions created by Chinese workers for Chinese workers, to explore their necessity in the lives of defenseless immigrant workers; then compare and contrast differing relations between workers and unions, ranging from supportive to negligent to oppositional; and finally conclude by investigating the current unionization trends among Chinese immigrant workers, and how these rates compare to other immigrant demographics.

Chinese Unions, for Chinese Workers

Chinese workers largely settled on the West Coast due to the earlier Gold Rush, establishing their own communities, and attracting even more immigrants to those areas. Following the Gold Rush, many Chinese workers took up low paying jobs, such as cigar making or working in laundromats. Unions were created for a variety of reasons, not only to provide economic benefits and protect vulnerable Chinese immigrants, but also to uphold culture and tradition among workers – Berkeley Professor Walter Fong writes:

“It is customary among the Chinese… to worship their dead at the grave… each member is expected to contribute a small sum of money for the expenses.”

This practice also applies to celebrating holidays, birthdays, and deathdays of Gods in Chinese religion, highlighting the extensive cultural services that unions provide to its members, on top of the usual economic benefits. Here, we can see that unions act as a preserving force for Chinese culture, intensifying the relationship between immigrant workers and labor unions. As Fong explains, these unions provide extensive benefits to its members, ranging from “[protecting] their members from being wronged by the white people”, “[uniting] against other Chinese who may take away their work”, “[settling] disputes among their own members”, “and to “keep up wages”. These four objectives of Chinese labor unions reflect its importance in the lives of Chinese laborers, not only providing them economic and social benefits, but also protection against external threats who may uproot their jobs or otherwise seek to exploit them. In this investigation, we can see that the relationship between Chinese workers and Chinese unions is very close, with workers depending on unions for a variety of benefits that are essential to their livelihoods, including cultural preservation. As such, unions played a far larger role than simply advocating for better economic conditions.

Assistance and Acceptance from the IWW

The relationship between Chinese workers and American unions was much less generally amiable: though the International Workers of the World (IWW aka Wobblies) was more favorable towards Chinese workers, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) took a much more hardline nativist approach, calling for the expulsion of all Chinese immigrants that eventually took form in the shape of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. First, on the positive side was the IWW; following Eugene Debs’ call for multiracial solidarity and opposition to racial discrimination, the IWW “consistently worked for cooperation of Asian and non-Asian workers… and that an Asian American constituency supported multiracial unionism and the IWW.” Due to its dedication to racial solidarity, the IWW was unique in its assistance provided to Asian workers, primarily in its social and political advocacy. This was demonstrated by J. H. Walsh, one of the “most astute Wobbly spokesmen for organizing Chinese and Japanese workers,” who traveled across the country “[defending] Asians as human beings, as union members, as stalwarts in strikes, and [making] a special pitch for their organization.” He enthusiastically defends their existence and dignity, arguing that they were just as dependable, if not more than white members. These interactions between the IWW and their immigrant constituencies show the positive relations that exist between Chinese workers and American unions. At a time where the Chinese were faced with hostility, violence, and the possibility of exclusion, the IWW rushed to their defense, giving them a political voice where no one else would. Through this advocacy, Walsh and the IWW managed to spur unionization rates among Asian workers, incorporating them into a small part of the mainstream labor movement. The IWW, however, wasn’t the only major labor organization in the US, and it certainly wasn’t representative of how all unions viewed Chinese workers.

Rejection and Opposition From the AFL and Most Other Labor Unions

The IWW stood in contrast to the AFL, “which refused to organize Asians and sought through legislation to excuse them from the country.” (Rosenberg) The concept of the “yellow peril” was widespread among West Coast labor unions, which only aggravated the pre-existing violent tendencies towards Asian workers. By excluding them from much of the mainstream labor movement, hostile groups also hindered the ability for workers to organize and advocate for themselves. Professor Glenn Omatsu states that the AFL “rose to national prominence with its campaign to ‘protect American jobs’… by expelling all Chinese and Japanese immigrants,” echoing the nativist sentiment popular at the time. Labor leaders then “united with politicians… to ban all immigration from Asia, to bar remaining immigrants from joining unions, and to lead mobs to beat… those who could not be banned, barred, or expelled.” This further emphasizes the hostility already faced by Chinese workers in the US, highlighting the negative relationships between immigrants and the mainstream labor movement. Though the IWW was staunch in its support of Chinese workers, it was an exception – most union leaders opposed the cheap, slave-like laborers that poured into the country, using violence to enforce their exclusion. This opposition stemming from labor unions was special in comparison to other forms of violence in that it actively barred Chinese workers from the institutions that would best support them in such an environment – without the help of unions, Chinese laborers were left to fend for themselves in a country that wanted them out or dead. Whilst the IWW represented the positive relationship between Chinese workers and unions, the AFL, along with most other labor unions, represented the strictly negative aspects, demonstrating that this relationship between workers and unions is largely adverse towards Chinese immigrants.

Negligence Throughout the Late 20th Century

In between support and opposition is negligence from labor unions. The late 20th century saw a massive increase in illegal immigration from China, which led to further conflict between immigrant workers and management that sought to further exploit them due to their vulnerable undocumented status. In these conditions, labor unions proved ineffectual, even useless at times – one such example is the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union: author Peter Kwong noted that the union “proved a surprisingly ineffective foe of unscrupulous sweatshop operators… of all the thousands of sweatshop violations, only eleven cases were referred to the attorney general’s office for criminal prosecution…” In addition, “there was no labor organizing to pressure the government to enforce labor laws” which have been in disrepair following deindustrialization and the passage of the Taft-Hartley Act. Unionization rates were at an all time low, the existing unions became a self-centered and out of touch bureaucracy, and there was no desire to increase their numbers again. Rather than advocating for greater economic benefits and working conditions, union leaders began to shift blame on the plight of the working class onto foreign competition, leading to “Chinese [union] members… picketing against their fellow workers in China and Hong Kong.” From the perspective of Chinese workers, these top-down unions provided little benefits to them, preferring to work closely with management rather than their own rank and file members to protect the union’s currently possessed benefits. As a result of this negligence, Chinese workers continued to face decades of exploitation by their employers. These experiences left a negative image in the minds of Chinese workers – not only have they been historically attacked by the likes of the AFL, but they continue to face dereliction from the institutions that were meant to protect them.

Modern Unionization Rates and Trends

In today’s economy, there has been an ever growing gap between the unionization rates of Chinese immigrants and other demographics; in the context of this essay, it may seem logical to conclude that past mistreatment has led to this decline among Chinese union membership, but culture and distrust have a bigger impact on this pattern. A study done by UC Irvine Professor Daniel Schneider found 3 factors that contributed to anti-union views held by Chinese immigrants: firstly, due to their experience with the state-run union in China, these workers “tended to view unions as ‘outside forces’ separate from workers”; secondly, recent patterns of Chinese immigration “has increasingly favored entrepreneurial and professional immigrants”, which naturally trends away from unionizing their workplace compared too blue-collar workers; and lastly, cultural norms within Chinese communities “encouraged deference to authority”, weakening the motivation for Chinese workers to unionize against their bosses. These elements stand in contrast to the other demographics examined in the study – Filipino immigrants, having positive experiences with unions in the Philippines, are far more likely to unionize in America; in addition, their culture revolving around labor militancy contributes to this pattern. As a result, not only are “[immigrant] Chinese workers… 43 percent less likely than native Whites to be union members”, but they are also leaving unions at higher rates than joining, reflecting their anti-union biases. Out of all tested demographics, Hispanic, Filipino, White, and Chinese, Chinese workers were the least likely to belong to a union, citing changing employment opportunities and political climates in China. In this period of immigrant Chinese laborers, the relationship between workers and unions is ever widening, with anti-union sentiments being the dominant perspective among Chinese immigrants.

Conclusion

Following a century of violence, oppression, and negligence, it is clear that the relationship between Chinese immigrant laborers and American unions is primarily negative. The sole exception to a labor environment overwhelmingly hostile to Chinese presence was in the case of the IWW; though the IWW tirelessly advocated for the rights and dignity for all workers, including Asian immigrants, most other unions rejected their speeches in favor of the “yellow peril” rhetoric that fueled nativist sentiments. AFL labor leaders have continuously attacked Chinese workers both physically and politically, culminating in the Chinese Expulsion Act. The violence didn’t stop there however, and Chinese workers continued to be exploited as a result of ineffectual labor unions. Besides the IWW, other positive experiences with unions came from Chinese headed unions, which dotted the West Coast during the early 20th century. These unions were more than just a tool for economic benefits, they were also institutions of culture, forms of protection, and a source of authority where none else were to be found. This gap in treatment between Chinese headed unions and local American unions reflects the racial divide between Asian immigrants and Caucasian Americans, a divide that extends to the pattern of anti-unionism among recent Chinese immigrants in comparison to other demographics. Should labor movements seek to resurrect Chinese unionization rates, they must reconcile both cultural and class differences that separate Chinese workers from other immigrant groups, taking care to address negative experiences with China’s state-run union and extending unionization efforts to highly skilled labor. Although J. H. Walsh’s vision of a racially integrative union has yet to come to fruition, the recent demand for unions may see a reversal of this trend for Chinese workers to finally be incorporated into the mainstream labor movement.

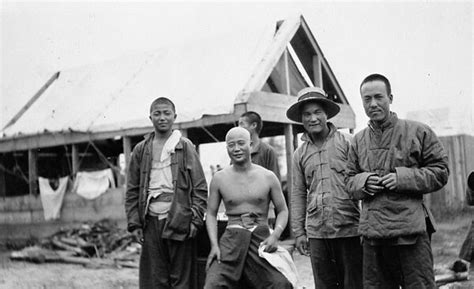

(Photo Credit: C. P. Meredith licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.)